Saving Olive Street Common

Olive Street Common has seen its fair share of changes and challenges over the decades, but possibly nothing more challenging than the debacle that it faced in 1998

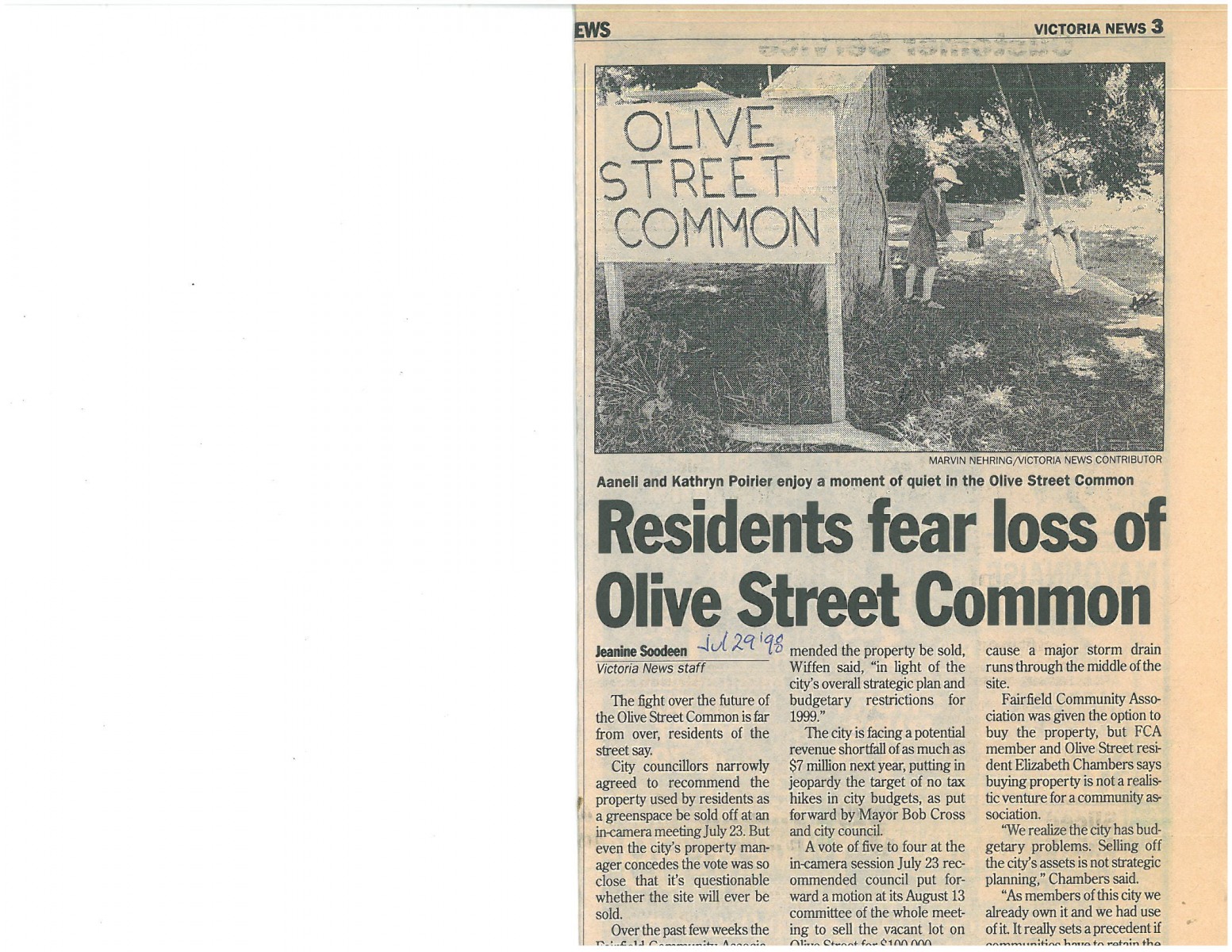

The lot was originally zoned for a single-family dwelling, but because of the captured stream running through it – which is now part of Victoria’s storm drain system – development had always been deterred. In 1985, the Fairfield Community Association even petitioned to have the lot removed from the city’s sale list. Because of this, the community did not think the lot was up for sale, but back in the 90s, as property values soared, interests in lots like Olive Street Common were renewed and the future of the common, for a short time at least, was in question.

1995 -1996

During the fall of 1995, the LifeCycles Project worked in partnership with the Fairfield Community Association sub-committee for Community Gardens to prospect Olive Street Common as a potential site for a community garden. Due to the nature of the site though, it was felt that the property was not suitable for this purpose. In consideration of the features of the site and neighbourhood interest, the LifeCycles Project instead looked at doing a study of the site to explore the possibility protecting it from development and preserving it as a cherished community space.

A neighbourhood community meeting was held on the 25th of February 1996, involving residents of Fairfield (primarily Olive St. residents) and LifeCycles. The meeting was arranged as an awareness and information session with the intention of generating discussion regarding potential options for the site. At this meeting, general concern was expressed over losing the value of the site by development, and interest was shown towards different potential community uses for the site. Some residents wanted it left as an “undeveloped” park site. Others talked with interest about the re-introduction of native plant species and preservation of bird habitat. Some talked of a natural children’s play area.

Newspaper Article Slideshow

It was agreed upon the LifeCycles DIGS Project could conduct a study of its current use and prepare an inventory along with a series of maps looking at the ecological make-up of the site. A steering committee was set up with the purpose of gaining official control of the site by the community from the city. Participants of the DIGS project carried out research for the creation of this Atlas . Ryan Good of the University of Victoria also prepared accompanying research: “Introduction to a Landscape Restoration Using Community consultation and Observations to Assess State and Suggest Improvements towards its Potential”.

March 1998

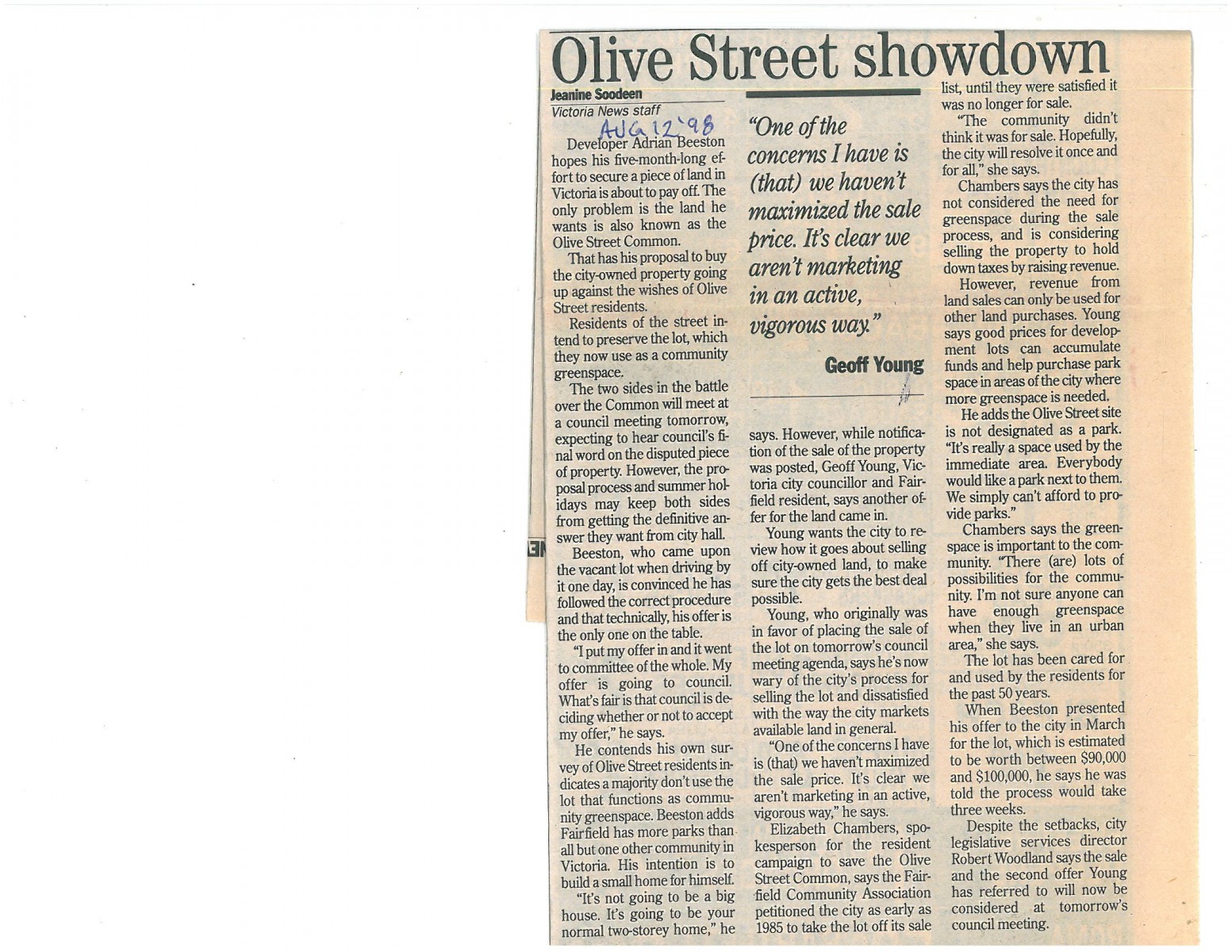

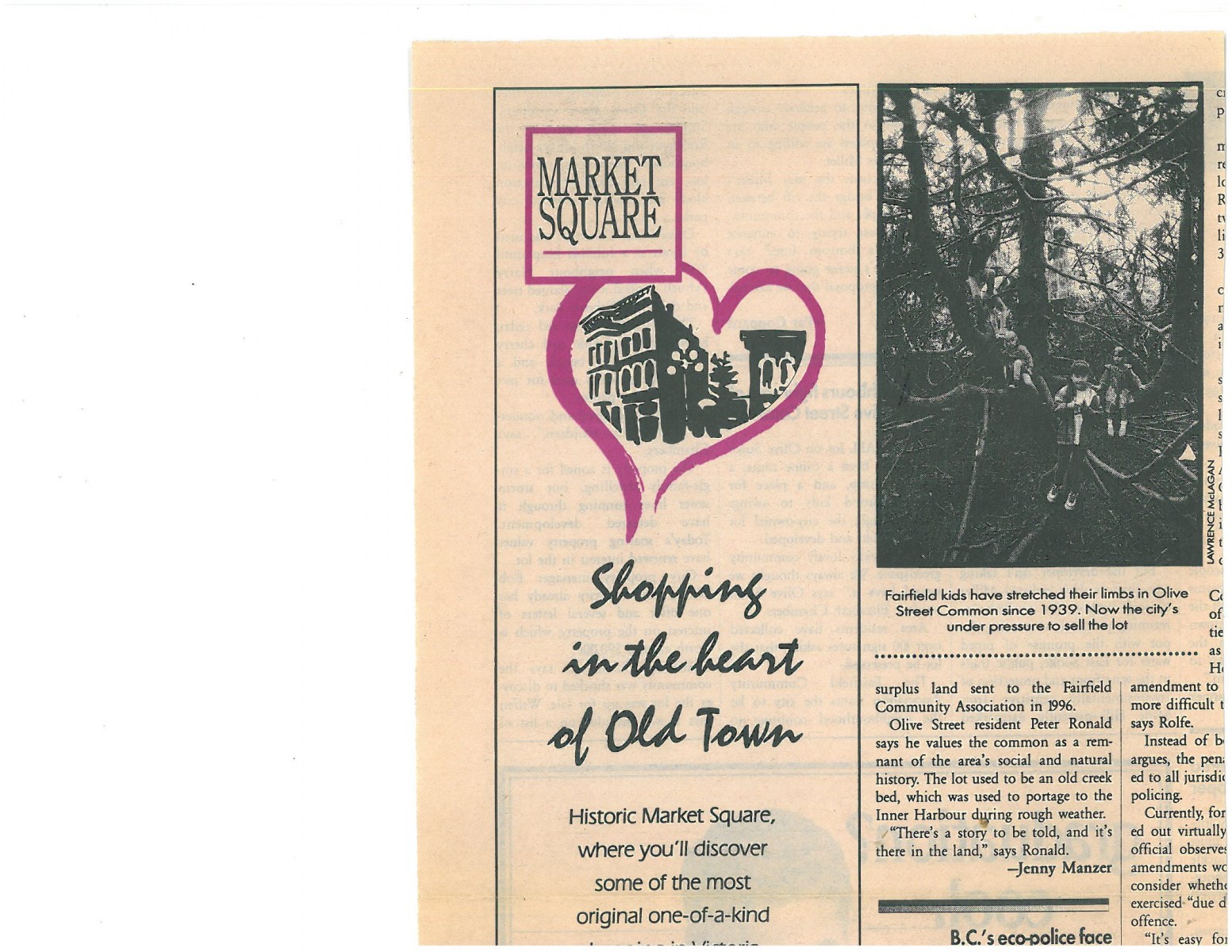

Adrian Beetson came upon the vacant lot one day while driving past. He saw the potential it had for development and put in an offer on the site, intending to build a small home for himself on it. He was told from the city that his offer of $90,000, which was tentatively accepted, would take no more than three weeks to process. From Beetson’s perspective, it seemed an ideal place to live and he presumed that the majority of residents did not use the lot. But he, of course, did not yet know the full history of the lot. Through no fault of his own, Beetson soon found himself in a five-month battle between the city and Fairfield residents to preserve the lot.

April – June 1998

During this time, more offers for the lot came in, prompting the city to review how it goes about selling city owned land while ensuring the city gets the best deal possible, but this would be the least of their worries. The city would soon be faced with the task of deciding whether or not Victoria tax payers should foot the bill for another Fairfield green space or see it sold at all. This decision, as the city would discover, would not be an easy process.

“This is an opportunity for the community to come together around the special gifts that have been discovered. This is an intimate experience; it is a place that brings the neighbourhood together.”

–John Campos, Fairfield Gonzales Community Association president in 1998.

As soon as Olive street residents found out about Beetson’s sale, signatures were collected to petition that the lot be preserved. The Fairfield Community Association also became involved, knowing that similar green spaces in other neighbourhoods, like Rockland and North Jubilee, were safe from auction, but were also not official city parks.

In June at a public hearing concerning the sale of the property, about a dozen people spoke for or against, with the majority of neighbours expressing their attachments to the small lot. Residents were shocked it was up for sale, having been under the impression that the lot had been taken off of the city’s surplus list in 1985. The city maintained, however, that it was no secret the lot was up for sale since in 1996, the Fairfield Community Association had been given a list of surplus land, which included the Olive Street Common.

Arguments from all sides were explored. Some council members said that Fairfield residents already have access to a considerable amount of green space, and stated Fairfield is the second most green community in Victoria. True as that may be, others argued that the green spaces in Fairfield, such as Beacon Hill Park and Clover Point, are in fact regional parks and are heavily used by people from all over the city year round as well as tourists, which is why unique lots like Olive Street Common, especially with its history, should be preserved. City councillors retaliated that, regardless, the Fairfield Community Association should have taken steps long ago to formalize Olive Street Common as a green space. In the end, the majority of city councillors voted to have the city staff look at possibly granting neighbours a nominal lease on the property, or other arrangements to keep it in its present state.

July 1998

By this point, about 800 signatures to save the common had been gathered. Issues around Beetson’s sale continued. The city was dealing with budgetary problems, potentially facing revenue shortfall of as much as $7 million for 1999. Up till now, the city was not considering the need for green space but instead, were considering selling the property to hold down taxes by raising revenue.

However, Victoria City cannot legally sell property to contribute to general revenue since, according to the Municipal Act, section 315.1, money generated by property sales must be placed as credit in a special fund. Consequently, the city intended for the sale from Olive Street Common, as well as any other similar lots, to accumulate into funds that could help purchase park space in areas of the city where more greenspace was needed. At the time, the city owned approximately 300-400 properties that could be sold.

But this was inconsequential to Olive street residents and locals, who knew the true community value of Olive Street Common and its special history. They continued to fight to preserve the lot and held a “painting protest” on the common. Two well-known artists, Robert Amos and Harry Heine, participated in the painting day. Harry Heine was a well-known marine artist and his son, Mark (also an artist), used to live on Olive street. Robert Amos in particular was known for documenting the city of Victoria with images.

“My family has enjoyed an affection for the Common. Children feel comfortable and safe in the heart of the neighbourhood.”

Eva Bild, resident of George Street.

City council largely chose to see the actions of the neighbourhood as only selfish and self-serving during this time, but Fairfield residents stood by what they were fighting for. Ever since Harry Tyhurst had taken it upon himself in 1945 to turn the lot from a dumping ground into a neighbourhood greenspace, the city was never asked to clean up, maintain, enhance or keep the property safe. The lot had been in the hands of the nearby residents for decades, nurturing it into a green space enjoyed by all, a space that the city had only ever seen as useless due to the storm drain running through it. To have it sold out from under them was the last thing Fairfield residents would ever have expected.

August 1998

In a council meeting mid-August, a final vote on the matter was held and city councillors voted five to two against selling the lot. Throughout the previous month’s process of being forced to evaluate how the city sells its properties, the city realized their own marketing process was at fault and the bidding process was flawed. This was the deciding factor in their vote, but also the fact that the captured stream under the property made it unsuitable for development did not help matters either.

As for the surplus land list, council voted to remove the common from the list, saying it had remained there due to clerical errors in previous years. Finally, the common was truly safe.

Conclusion

After the August meeting, the city began negotiations with the Fairfield Community Association on the best future use of the land, and it became formalized as a green space common. Ultimately, the Olive Street Common debacle raised questions on how the city sells property, paving the way for an overhaul to be done on city owned property. The city set out to review all city owned lots and their suggested uses, as well as prepare an extensive report on how the city goes about selling city owned property.

Victoria City as a whole is served by the preservation of green spaces because they foster a strong sense of community in their neighbourhoods, which is something any and all cities should strive for.

Olive Street Common has seen many picnics, plays, and street parties. It’s been the inspiration for children’s imaginations, turning the patch of grass at the rear of the property into ‘the back meadow’ and hosting a ‘secret passage’ from the meadow to the large climbing tree in the middle of the property. The lot is home to a driftwood bench and a swing, both installed by Olive street residents. There are Red Cedars, Hawthorns, Ash trees, apple and cherry trees throughout the lot. A precious ‘lost stream’ of Victoria still runs through it underground, hailing from a time when First Nations people fostered the land.

Remnants of the Fairfield area’s social and natural history are what brings value to places like Olive Street Common. As former Olive street resident Peter Ronald once said, “There’s a story to be told, and it’s there in the land.” Thanks to Olive street residents and Fairfield locals, Olive Street Common continues to tell its story today. There is a timeless quality to the common; people come and go, controversy promotes challenges, but the common perseveres and continues to bring beauty, tranquility, and happiness to all who choose to stop by.